I am the eldest in a family of twelve. I had dreams, I had ambitions, because I strove even in boyhood after learning, after expression. But because I had love (I am proud to say this) I drowned all my ambitions of a brilliant career and gave my life for my family. This entailed entering into a life which was not calculated to build up the artistic career. I became a coal-miner. I have spent fourteen years of my life down in the deep eternal shadows of the mine, working with rough men with hearts like diamonds, sweating, toiling, fighting death daily, until, a dreamer by temperament, I am like a Titan in my capacity for work. I feared no one at my work, I fear no physical work now. Yet even in that environment my soul craved for learning, and with limbs aching with physical weariness and pain, I have sat up until the hours of midnight devouring the books that I had been able to buy after many weeks’ saving of my spending pittance.

So wrote Will Streets to his friend W H Wright on 13th May 1916.

So wrote Will Streets to his friend W H Wright on 13th May 1916.

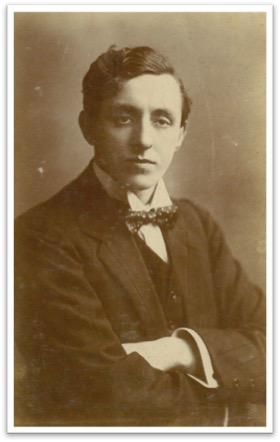

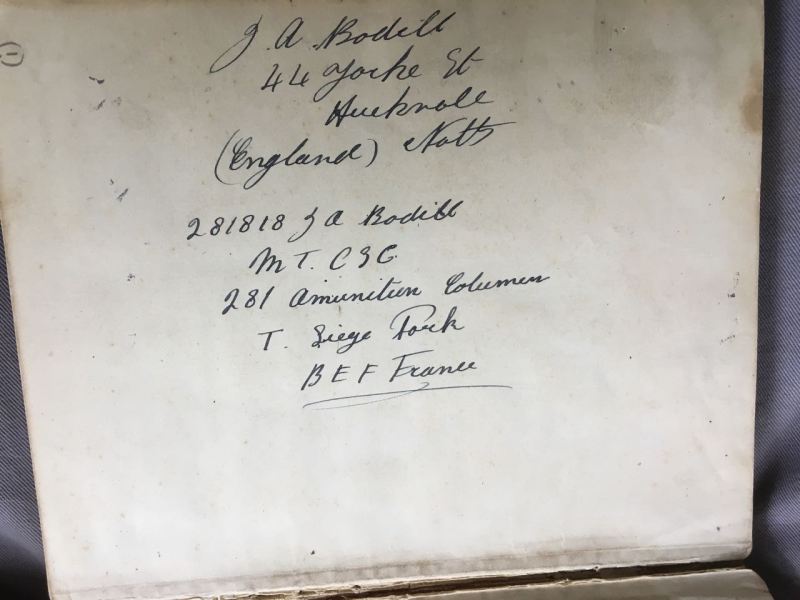

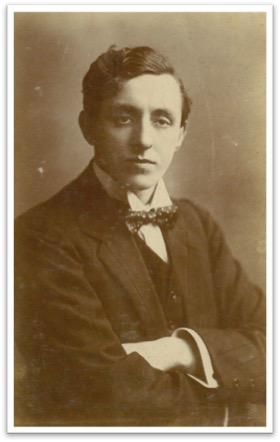

Sergeant John William Streets, of the 12th Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment (aka the Sheffield Pals) is unusual for a World War I soldier from the Worksop area. A miner, Methodist and poet; Will Streets left behind a stunning collection of letters which tell his story. Not only his life as a soldier in the Sheffield Pals, but his home life is told in his own words.

Will is best known for his poetry, in particular his sonnet-sequence, The Undying Splendour, published posthumously by his younger brother Ben. The sonnet which best sums up his life and death is An English Soldier.

He died for love of race: because the blood

Of Northern freeman swell’d his veins: arose

True to tradition that like mountain stood

Impregnable, crown’d with its pathless snows.

When broke the call, from the sepulchred years

Strong voices urged and stirr’d his soul to life;

The call of English freeman fled his fears

And led him (their true son) into the strife.

There in the van he fought thro’ many a dawn,

Stood by the forlorn hope, knew victory;

Proud, scorning Death, fought with a purpose drawn,

Sword-edged, defiant, grand, for Liberty.

He fell: but yielded not his English soul:

That lives out there beneath the battle’s roll.

When asked what inscription Will’s mother Clara Streets would like on her son’s headstone in the Euston Road Cemetery No. 4 (Colincamps, France), she requested a variation on Will’s own words: “I fell: but yielded not my English soul, that lives out here beneath the battle’s roll”.

On 10th June 1916, Will wrote a poignant letter to his younger brother, Ben; in which he included the “sonnet-sequence that I have been working at lately”. Will’s letter continued with a sadness and request that his brother keep his secret. “The next month or two will see me in a position to endeavour to have a book printed, or see me beneath the sweet soil of France. I cannot tell you why. Only accept the statement and keep it to yourself.” Ben Streets could not have known what was coming. Less than a month later the poet, miner, soldier from Whitwell was one of the 19,240 who fell on the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

All letters courtesy of Nottinghamshire Archives. Collection reference: DD1499.

So wrote Will Streets to his friend W H Wright on 13th May 1916.

So wrote Will Streets to his friend W H Wright on 13th May 1916.